What is an ammonite ? Part 1

With this text, I start a series of 5 articles on the fossils of the extinct subclass Ammonoidea, belonging to the class of cephalopods. Ammonoids, or ammonites, are obviously not “sea snails”, even though their shell form resembles that of Gastropods : like all cephalopods, ammonites are thought to have a head with 2 camera-type eyes 1 and several tentacles ; they were nectonic organisms swimming in open water, not crawling on the seafloor. The first ammonites appeared nearly 400 million years ago in the Devonian. Ammonites were widespread in seas and oceans for about 334 million years before becoming completely extinct 66 million years ago. Ammonites are of great importance in paleontological research : they are some of the most abundant fossils, especially in Mesozoic rocks. Their spiral shells are common in many rocks, for example the limestones and marls of the Jura mountains (Jurassic-Cretaceous), where we also find calcitic plates called Aptychi, which are elements of ammonoid lower jaws.

Albian (Lower Cretaceous) ammonites from the Jura mountains.

Quenstedtoceras flexicostatum. ammonite. Lower Oxfordian (Upper Jurassic), Vaud, Switzerland. Image from the gallery

Laevaptychus sp., ammonite lower jaw element (Aspidoceratidae indet.). Lower Oxfordian (Upper Jurassic), Vaud, Switzerland. Image from the gallery

The term «ammonite» was already employed in ancient times. It is linked to the Ancient Egyptian god Amun, who was often represented with ram horns that indeed look like ammonites.

Ammonite Cantabrigites aff. cantabrigense. Albien (Crétacé inférieur), Jura. Image from the gallery

Ammonite Cantabrigites aff. cantabrigense. Albien (Crétacé inférieur), Jura. Image from the gallery

For a long time, there was no scientific description for the formation of fossils. They were rarely linked to ancient life, and more often thought to appear spontaneously in rocks. The first to identify ammonites as extinct cephalopods was Robert Hooke (1635-1703). Hooke compared the ammonites he had found with Nautilus, a modern cephalopod with a spiral shell.

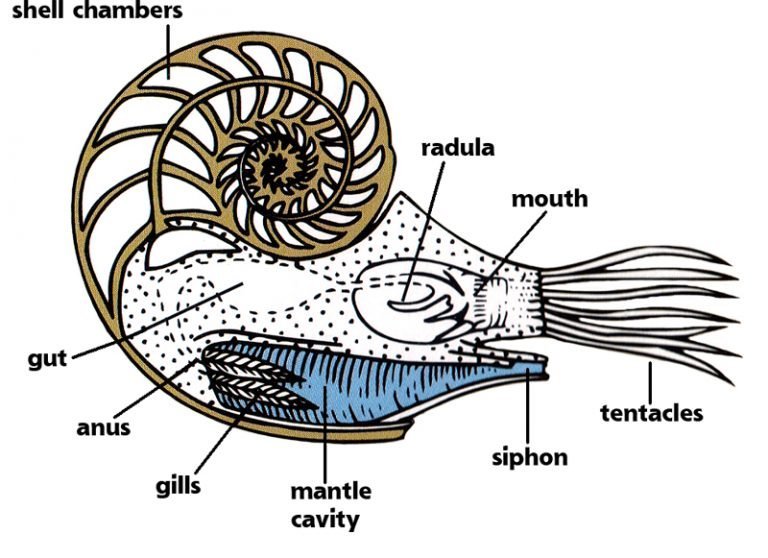

Extant Nautilidae use their shell to maintain neutral buoyancy at different depths. The inner whorls of their shells are divided into hollow sections, called hydrostatic chambers. The end of the shell (living chamber) is undivided because it contained the soft body, and ends with an aperture. The chambered part is called phragmocone. Hydrostatic chambers contained a mix of air and water. A tube, called siphon or siphuncle, runs through every chamber ; its function is to modify their air/water content. Removing water from the hydrostatic chambers made the shell lighter that the surrouding water and allowed move upwards while pumping air out and adding water made the mollusc sink downwards.

Extant Nautilus pompilius Image source.

Cut of the shell of an extant Nautilus Image source.

R. Hooke observed the same features in ammonite fossils. They also had a shell divided into chambers, although the wall between them is much more complex than in extant Nautilus. The last whorls, where preserved, are free of chambers. And in some specimens, even the siphuncle is preserved. Robert Hooke didn’t know its function, however he observed it on some of his fossils.

Dorsoplanites dorsoplanus. ammonite. Moscow, Upper Jurassic, around 149 years old. Note the siphon on the right picture. Image from the gallery

The discovery of the nature of ammonites and other fossils made Robert Hooke formulate several hypotheses. He argued that organic substances were replaced by mineral substances from the surrounding environment, which lead to the formation of fossils. He also noted that most fossils were marine, but they were found at places very far from the sea and above the sea level; he concluded that seas existed there a long time ago, but disappeared because of structural changes in the earth’s crust. Lastly, he proved that some fossils belonged to extinct groups, and supposed that living organisms could change in the course of an evolution.

One of Robert Hooke’s illustrations of ammonites (1).

Ammonite fossils are useful in geology. Their well-developed classification and their rapid evolution allow to use them as time markers to date sedimentary rocks. Observing the migrations of various ammonite species also yield information on marine paleogeography, like the existence of openings or currents.

Source: Mironenko, A.A., 2015: Wrinkle layer and supracephalic attachment area: implications for ammonoid paleobiology. Bulletin of Geosciences 90(2): 389–416.

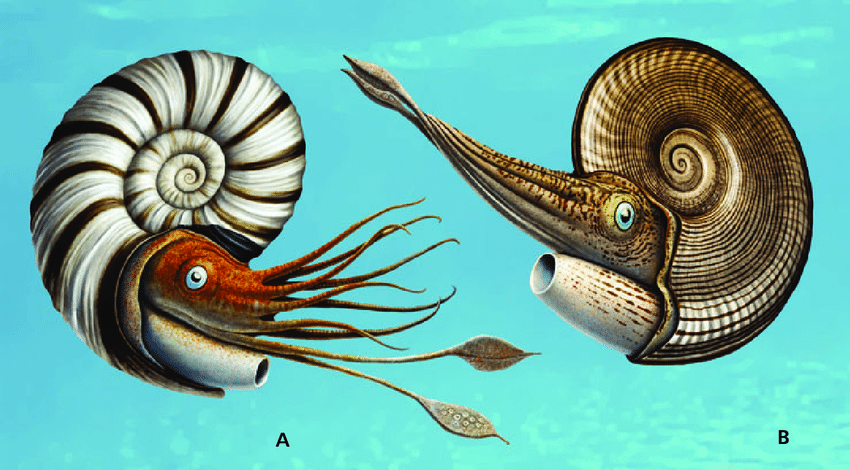

The image above is a reconstruction of ammonites. It is based on modern scientific data about ammonoid anatomy, including soft body anatomy. I will discuss the accuracy of different reconstructions in another article.

The elongated tube below the head is the hyponome, also named funnel or siphon (not to be confused with the siphuncle). It is a locomotory organ common to all cephalopods. Cephalopods eject water from the mantle cavity through the hyponome, creating a reactive force that pushes the mollusc in the opposite direction.

It is thought that propulsion was the main mean of active movement of ammonites, and allowed them to swim moderately fast. However, some species could also swim by moving their tentacles. Lastly, some ammonoids were not adapted to active swimming, and were carried by water currents.

From the point of view of evolution, ammonites are closer to Coleoidea than to Nautiloidea. It can seem unlikely, considering that I just said that it is precisely the comparison with nautilids that allowed to identify ammonoids as cephalopods. It turns out the evolution of Coleoidea and Ammonoidea was divergent: while ammonites kept and perfected their outer shell, the shell in coleoids first became internal, then it lost its importance, causing at first the disappearance of the phragmocone (as in calmars) and then the complete loss of the shell in octopuses. Nautilids, on the other hand, kept a spiral external shell as well. Caracters common to ammonites and nautilids are either inherited from primitive common ancestors or as s result of convergent evolution. The origin of ammonoids, as well as their relation to extant coleoids, will be discussed in the next publication.

Belemnite fossil (Cephalopoda; Coleoidea), Jurassic. The phragmocone (gray part) is located inside the soft body.

Don’t miss : Paleobiology and evolution of Ammonoidea . Part 2

Bibliography

- Hooke R., Discourse on Earthquakes. The posthumous works of Robert Hooke. 1705. p. 279-289.

- Ogura A., Yoshida M., Moritaki T., Okuda Y., Sese J., Shimizu K.K., Sousounis S., Tsonis P. A., 2013 : Loss of the six3/6 controlling pathways might have resulted in pinhole-eye evolution in Nautilus. // Scientific Reports. 2013. Vol. 3. art. 1432.

-

Extant Coleoidea have well-developed eyes, comparable to the human eye, but with accommodation regulated by horizontal movement of the crystalline lens. Nautilids have very simple eyes without cornea or crystalline lens that don’t allow a good vision. Genetic studies show that the eyes of Nautilus were simplified in the course of evolution, while primitive cephalopods had eyes comparable to those of Coleoidea (2). Therefor it is thought thought that ammonoids had a good vision, especially considering that they inhabited shallow well-lit epipelagic zones and that many of them were active predators. ↩︎