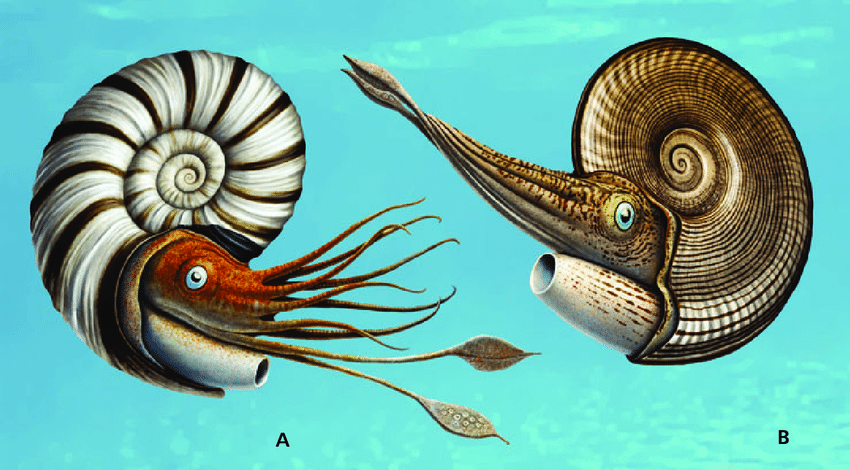

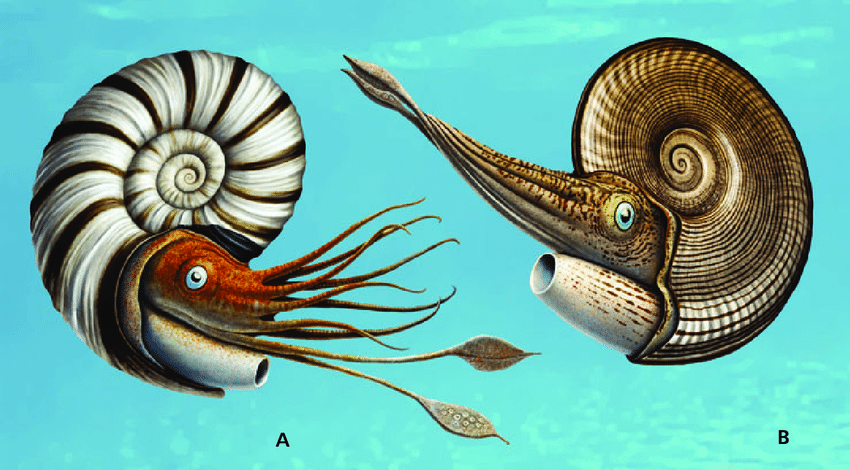

With this text, I start a series of 5 articles on the fossils of the extinct subclass Ammonoidea, belonging to the class of cephalopods. Ammonoids, or ammonites, are obviously not “sea snails”, even though their shell form resembles that of Gastropods : like all cephalopods, ammonites are thought to have a head with 2 camera-type eyes and several tentacles ; they were nectonic organisms swimming in open water, not crawling on the seafloor. The first ammonites appeared nearly 400 million years ago in the Devonian. Ammonites were widespread in seas and oceans for about 334 million years before becoming completely extinct 66 million years ago. Ammonites are of great importance in paleontological research : they are some of the most abundant fossils, especially in Mesozoic rocks. Their spiral shells are common in many rocks, for example the limestones and marls of the Jura mountains (Jurassic-Cretaceous), where we also find calcitic plates called Aptychi, which are elements of ammonoid lower jaws.

Albian (Lower Cretaceous) ammonites from the Jura mountains.

Quenstedtoceras flexicostatum. ammonite. Lower Oxfordian (Upper Jurassic), Vaud, Switzerland. Image from the gallery

Laevaptychus sp., ammonite lower jaw element (Aspidoceratidae indet.). Lower Oxfordian (Upper Jurassic), Vaud, Switzerland. Image from the gallery

The term «ammonite» was already employed in ancient times. It is linked to the Ancient Egyptian god Amun, who was often represented with ram horns that indeed look like ammonites.

Ammonite Cantabrigites aff. cantabrigense. Albien (Crétacé inférieur), Jura. Image from the gallery

Ammonite Cantabrigites aff. cantabrigense. Albien (Crétacé inférieur), Jura. Image from the gallery

For a long time, there was no scientific description for the formation of fossils. They were rarely linked to ancient life, and more often thought to appear spontaneously in rocks. The first to identify ammonites as extinct cephalopods was Robert Hooke (1635-1703). Hooke compared the ammonites he had found with Nautilus, a modern cephalopod with a spiral shell.

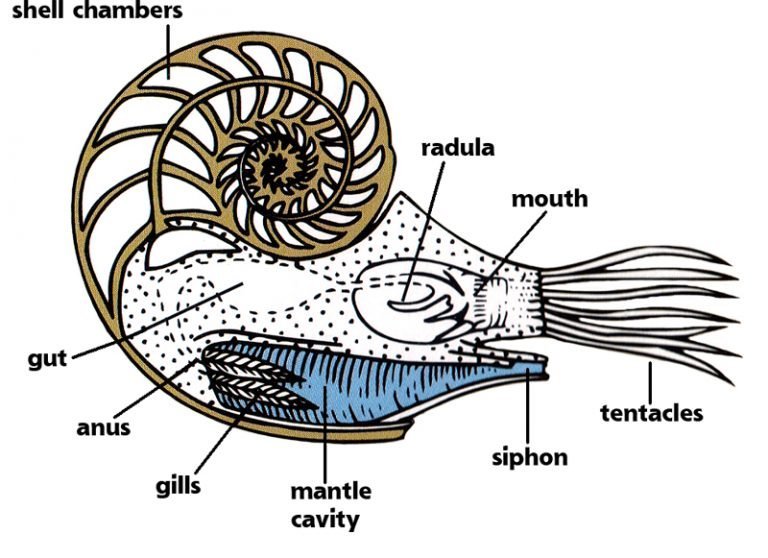

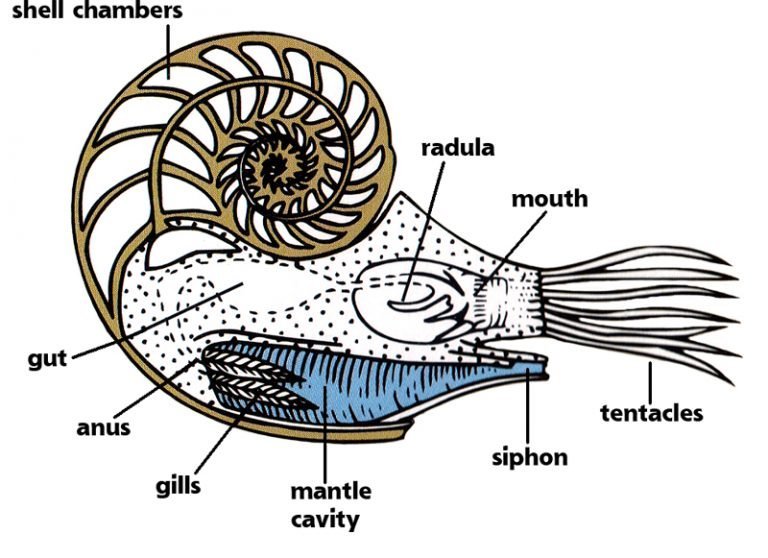

Extant Nautilidae use their shell to maintain neutral buoyancy at different depths. The inner whorls of their shells are divided into hollow sections, called hydrostatic chambers. The end of the shell (living chamber) is undivided because it contained the soft body, and ends with an aperture. The chambered part is called phragmocone. Hydrostatic chambers contained a mix of air and water. A tube, called siphon or siphuncle, runs through every chamber ; its function is to modify their air/water content. Removing water from the hydrostatic chambers made the shell lighter that the surrouding water and allowed move upwards while pumping air out and adding water made the mollusc sink downwards.

Extant Nautilus pompilius Image source.

Cut of the shell of an extant Nautilus Image source.

R. Hooke observed the same features in ammonite fossils. They also had a shell divided into chambers, although the wall between them is much more complex than in extant Nautilus. The last whorls, where preserved, are free of chambers. And in some specimens, even the siphuncle is preserved. Robert Hooke didn’t know its function, however he observed it on some of his fossils.

Dorsoplanites dorsoplanus. ammonite. Moscow, Upper Jurassic, around 149 years old. Note the siphon on the right picture. Image from the gallery

The discovery of the nature of ammonites and other fossils made Robert Hooke formulate several hypotheses. He argued that organic substances were replaced by mineral substances from the surrounding environment, which lead to the formation of fossils. He also noted that most fossils were marine, but they were found at places very far from the sea and above the sea level; he concluded that seas existed there a long time ago, but disappeared because of structural changes in the earth’s crust. Lastly, he proved that some fossils belonged to extinct groups, and supposed that living organisms could change in the course of an evolution.

One of Robert Hooke’s illustrations of ammonites (1).

Ammonite fossils are useful in geology. Their well-developed classification and their rapid evolution allow to use them as time markers to date sedimentary rocks. Observing the migrations of various ammonite species also yield information on marine paleogeography, like the existence of openings or currents.

Source: Mironenko, A.A., 2015: Wrinkle layer and supracephalic attachment area: implications for ammonoid paleobiology. Bulletin of Geosciences 90(2): 389–416.

The image above is a reconstruction of ammonites. It is based on modern scientific data about ammonoid anatomy, including soft body anatomy. I will discuss the accuracy of different reconstructions in another article.

The elongated tube below the head is the hyponome, also named funnel or siphon (not to be confused with the siphuncle). It is a locomotory organ common to all cephalopods. Cephalopods eject water from the mantle cavity through the hyponome, creating a reactive force that pushes the mollusc in the opposite direction.

Image source.

It is thought that propulsion was the main mean of active movement of ammonites, and allowed them to swim moderately fast. However, some species could also swim by moving their tentacles. Lastly, some ammonoids were not adapted to active swimming, and were carried by water currents.

From the point of view of evolution, ammonites are closer to Coleoidea than to Nautiloidea. It can seem unlikely, considering that I just said that it is precisely the comparison with nautilids that allowed to identify ammonoids as cephalopods. It turns out the evolution of Coleoidea and Ammonoidea was divergent: while ammonites kept and perfected their outer shell, the shell in coleoids first became internal, then it lost its importance, causing at first the disappearance of the phragmocone (as in calmars) and then the complete loss of the shell in octopuses. Nautilids, on the other hand, kept a spiral external shell as well. Caracters common to ammonites and nautilids are either inherited from primitive common ancestors or as s result of convergent evolution. The origin of ammonoids, as well as their relation to extant coleoids, will be discussed in the next publication.

Belemnite fossil (Cephalopoda; Coleoidea), Jurassic. The phragmocone (gray part) is located inside the soft body.

Don’t miss : Paleobiology and evolution of Ammonoidea . Part 2

- Hooke R., Discourse on Earthquakes. The posthumous works of Robert Hooke. 1705. p. 279-289.

- Ogura A., Yoshida M., Moritaki T., Okuda Y., Sese J., Shimizu K.K., Sousounis S., Tsonis P. A., 2013 : Loss of the six3/6 controlling pathways might have resulted in pinhole-eye evolution in Nautilus. // Scientific Reports. 2013. Vol. 3. art. 1432.

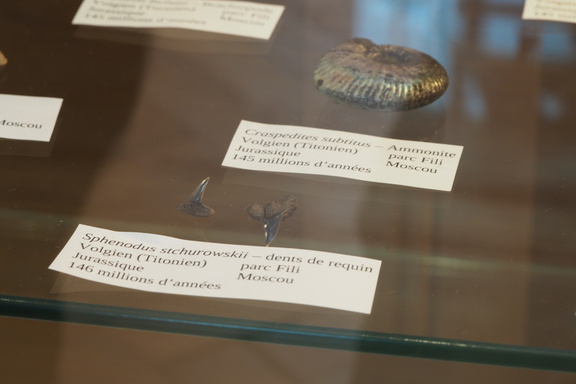

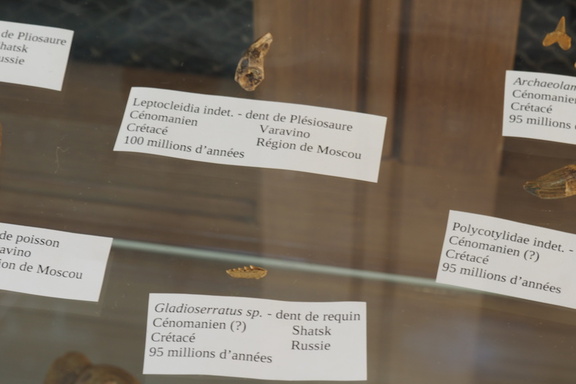

This was the first exhibition of my collection; up to now all the specimens were kept in boxes in my room (and until 2022 in Moscow I had a room where I exposed some fossils). My dad once told me that I could get a room for one day to organize an exposition. Therefor, I started to prepare the specimens and the lecture that I was going to read on the exposition.

Some specimens from my collection exposed in Moscow, 2019.

I already started to prepare the exposition in early March. In march, I already chose the specimens I wanted to expose and wrote the text for my presentation, in which I only made some correction in May. However, many things that had nothing to do with the exposition actually disturbed me and took most of my time. The exposition took place on the 25 May. As I understand now, I should have started preparation even earlier, so I could focus on organization the last weeks before the exposition, and some last-moment organizations problems could have been avoided. As an example of such a problem, I put number 9 instead of 11 as the address on the exposition affiche, and noticed it when it was already sent. If I had enough time, I could have read it 10 times before sending.

I told about the exposition to many acquaintances, and also asked a teacher from my school to send the affiche of the exposition to the whole school, which he did.

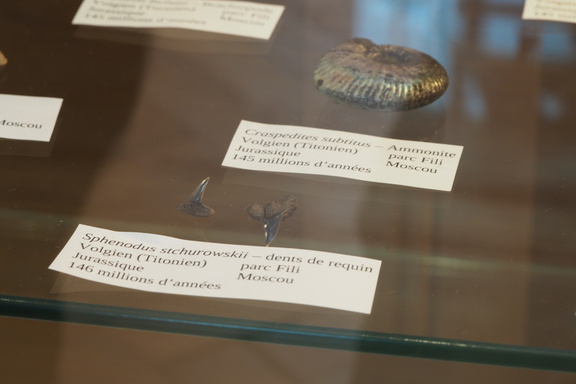

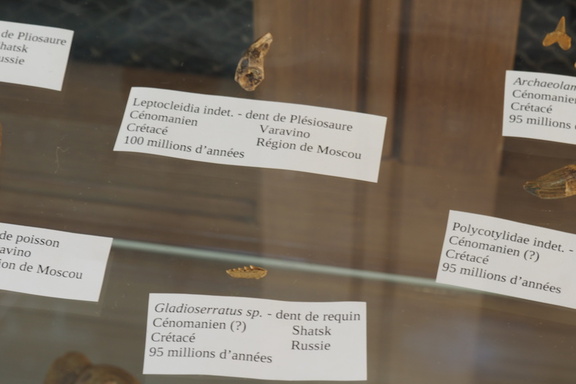

I exposed fossils from Russia as well as recent specimens from France and Switzerland: shark teeth (from the Carboniferous, Jurassic, Cretaceous and Neogene), Mesozoic marine reptiles’ bones, Jurassic and Cretaceous ammonites, bivalves, gastropods, brachiopods, bryozoans and some other fossils. They were disposed in vitrines that I borrowed at the SGAM. Some specimens had descriptions and images. Everyone knows what sharks are, but few people know about brachiopods and bryozoans.

I disposed the specimens in 2 vitrines.

I actually should have prepared more vitrines to make the specimens and labels more visible.

Ichthyosaur forelimb

Bryozoans (early Carboniferous) and their description.

The presentation was divided into 5 parts:

- Introduction part. What is paleontology. How fossils are preserved.

- Geological history of Switzerland. This part was about ancient seas and oceans in Switzerland : the Tethys ocean and the North Alpine foreland basin.

- About expeditions, how and where to search fossils.

- Scientific significance of fossils. I discussed muscle imprints on ammonite fossil shells, shark evolution, biostratigraphy, determination of ancient environmental conditions using fossils.

- Some addresses of geological and paleontological clubs in Switzerland, and some paleontological websites.

I should have added a part about fossil preparation, but this will be for another time.

Roughly 15 persons came for the presentation. It looked like everyone found it interesting, there were some questions. And there was around 20-25 people on the exposition. Three people from my school came as well, and one of them was very impressed to see shark teeth that are 330 million years old. I must say that the exposition went well, and it is always good for the specimens to get out of their boxes.

Leonid Sergeyevich Glickman was a paleontologist specialist of shark evolution. His studies made a revolution in the classification of elasmobranchs. He developed new research methods based on dental morphology, which led to remarkable advancements in the study of shark evolution.

Leonid Glickman was born on the 23rd January 1929 in Leningrad. His father was a well-known chemist – Serguei Abramovitch Glickman. In 1939, Glickman and his parents moved to Kiev. His mother died just before the war. In 1941, Leonid Glickman and his father were evacuated in Tashkent. At the end of the war, they moved to Saratov, where his father was appointed chief of the colloidal chemistry department of the Saratov State University. At the age of 18, L. S. Glickman graduated from school and entered at the biology and soils department of the SSU.

The Saratov region is well-known for its upper cretaceous deposits delivering a rich elasmobranch fauna. By the end of school, Leonid Glickman already collects shark teeth. During his studies at the SSU he gathers a collection of several tens of thousands of vertebrate fossils from the Saratov cretaceous : sharks (teeth), chimaeras (teeth and bones), bony fishes (teeth, bones and scales), ichtyosaurs (vertebrae), plesiosaurs (teeth and bones), and a jaw fragment and a partial skeleton of pterosaurs [1].

L. S. Glickman gets in touch with L. I. Hozatskiy, paleontologist, specialist of turtles at the Leningrad State University. In 1950, Glickman moves to Leningrad, and L. I. Hozatskiy helps for his transition to the LSU. Leonid Glickman graduates from University in 1952, with a paper called «The Upper Cretaceous Marine Vertebrates from the Volga bank near Saratov», which will be the basis of his first scientific paper [1].

L. S. Glickman wants to continue his research on elasmobranch evolution. But the beginning of the 50s is the peak of stalinian antisemitism, and despite his brilliant studies, finding a job with the name Glickman turned out to be hard and he is hired in 1952 only as a secretary of the A. P. Karpinskiy Geological Museum, where he also works as a guide. In 1953, he takes part in two expeditions where he collects fossil shark teeth. Then, in 1954, on the request of the Geological Institute of the SSU, Glickman works on upper cretaceous sharks (Glickman, 1954) and collects teeth from the Saratov and neighboring regions. In 1954, Glickman obtains a scientific post at the A. P. Karpinskiy Museum. At the same time, he starts to prepare his candidate* thesis. During this period of his life, he publishes numerous papers about sharks evolution. On the 25 December 1958, he defends his thesis «On the classification of sharks» with success and obtains the degree of candidate in biology. This thesis will be the base of his monograph «Paleogene sharks and their stratigraphic value» [5], a revolution in the classification and the study of sharks. In 1964, he also publishes the «Elasmobranchii» section in the «Fundamentals of Paleontology», a reference guide for soviet paleontologists [6].

L. S. Glickman with the skull of an extant Carcharhinus , 1960-s

L. S. Glickman actively collects fossil shark teeth material. He studies the stratigraphy of cretaceous and cenozoic deposits of Moscow region, Volga, Kazakhstan, central Asia, and collects detailed shark teeth material from different horizons. Most of his expeditions were not funded, but paid by Glickman himself, and in 1960, during one of his expeditions, he even lost his salary for a month, because his direction considered that he was not at work.

L. S. Glickman during an expedition in Kasakhstan, 1960-s.

In 1970, Leonid Glickman moves to Vladivostok, where he will work 10 years in the Marine Biology Institute. Here, he wanted to study modern sharks, but he doesn’t really have this opportunity. He actually studies salmonids and gives consultations to other researchers in evolutionary biology. Glickman also prepares his doctor thesis «The evolutionary patterns of cretaceous and cenozoic lamnoid sharks». He attempts to obtain the degree of doctor in geology in 1972 at the geological department of the Moscow State University. This attempt wasn’t successful, and he makes another one in 1974 at the Institute of Paleontology in Moscow. This time, he tries to obtain the degree of doctor in biology. This try also fails, and one of the judges, V. V. Menner, recommends to make some improvements in the thesis. In 1976, Glickman tries for the last time to defend his thesis at the Marine Biology Institute, with the support of V. V. Menner. However, the same year, Glickman takes part in an expedition in Kamchatka for 6 months, and the defense doesn’t take place. In 1980, his doctor thesis will be published under the name «Evolution of cretaceous and cenozoic lamnoid sharks» [7].

At the end of the 70s, L. S. Glickman disagrees more and more with his direction at the Marine Biology Institute. He leaves Vladivostok and comes back to Leningrad. At the same time, his collection is transferred to the Darwin Museum in Moscow, where it is currently kept. Being very poor, Glickman has to work as a security agent in a fabric, and he had a hip fracture that wasn’t looked after. However he still publishes papers about sharks (Glickman and Zhelezko, 1985, Glickman and Dolganov, 1988a, 1988b, Glickman and Averianov, 1998 and other).

In 1999, Glickman takes part in his last expedition in Kazakhstan. He dies a bit later, on the 31 January 2000, at the age of 71.

* Candidate - a title attributed for a thesis to researchers in USSR and Russia. The title “doctor” is similar to candidate and is attributed for a second thesis

Since the very beginning of his studies, Glickman chooses the evolution of elasmobranchs as his specialization. He seeks to develop new research methods. He gathers a great quantity of fossil shark teeth and studies extant shark remains kept in museums. The study of this material allowed to draw important conclusions about the systematics and the evolution of sharks.

Glickman gathered a collection estimated at around 200 000 specimens [4] of fossil shark teeth from the eastern Europe and central Asia, collected by Glickman himself or by other scientists, and also shark teeth collected from the floor of the Indian and Pacific oceans on the research stations «Vitiaz», «Ob» and «Lomonosov». He also incorporated the collections of A. S. Rogovitch, I. F. Sinzov and other scientists, saved from the liquidation of the A. P. Karpinskiy Geological Museum. The collection is kept in the Darwin Museum in Moscow.

L. S. Glickman with his collection of fossil shark teeth, 1950-s.

In 1970-1980, Glickman studied the salmonids and made some hypotheses on their evolution.

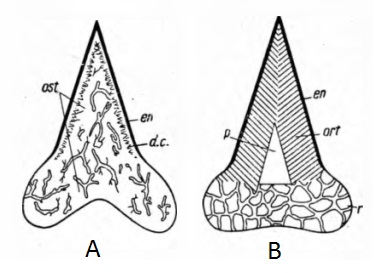

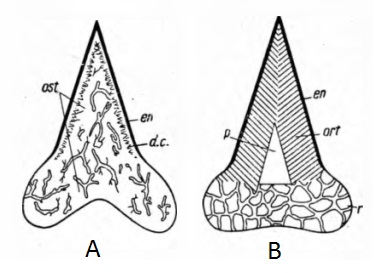

Leonid Glickman published 4 monographs (Glickman, 1964a, 1964b, 1980, Glickman et al., 1987) and 33 scientific papers. Glickman’s main concept is his elasmobranch classification. He noticed some fundamental differences in the organization of the neurocranium [7], the jaws and the dentition [5] of lamnoid sharks and other elasmobranchs. Additionally, the teeth of lamnoid sharks are made of osteodentin (a bone-like dentin tissue), while other sharks have a layer of ortodentin under the enameloid, and a pulpar channel (Fig. 1). These observations made Glickman separate the lamnoid sharks from other extant sharks and rays, and state their affinity with extinct osteodont-toothed elasmobranchs. Based on dental histology, he divided elasmobranchs in two infraclasss : Ortodonts and Osteodonts [5]. This division is confirmed by the similarity of cranial anatomy of Carcharhini (see part “Classification of sharks after Glickman, 1964a”) and Xenacanths (freshwater paleozoic sharks that Glickman supposed to be the ancestors of Carcharhini), and the similar organization of the neurocranium of Chlamydoselachus[7].

Subclass Еlasmobranchii

- Infraclass Orthodonta

- Superorder Cladoselachii

- Order Cladoselachida

- Fam. Сladoselachidae

- Fam. Denaeidae

- Order Сladodontida

- Fam. Сladodontidae

- Fam. Symmoriidae

- Fam. Tamiobatidae

- Superorder Xenacanthi

- Superorder Polyacrodonti

- Superorder Chlamydoselachii

- Superorder Carcharini

- Order Hexanchida

- Suborder Hexanchoidei

- Suborder Heterodontoidei

- Order Squatinida

- Suborder Echinorhinoidei

- Suborder Squaloidei

- Fam. Squalidae

- Fam. Dalatiidae

- Fam. Cetorhinidae

- Suborder Squatinoidei

- Suborder Ginglymostomatoidei

- Suborder Pristiophoroidei

- Suborder Rajoidei

- Superfam. Rhinobatoidea

- Fam. Rhinobatidae

- Fam. Asterodermatidae

- Fam. Platyrhinidae

- Superfam. Pristioidea

- Fam. Pristidae

- Fam. Torpedinidae

- Superfam. Rajoidea

- Superfam. Myliobatoidea

- Fam. Myliobatidae

- Fam. Trygonidae

- Fam. Hypolophidae

- Order Carcharhinida

- Fam. Palaeospinacidae

- Fam. Scyliorhinidae

- Fam. Triakidae

- Fam. Carcharhinidae

- Fam. Sphyrnidae

- Infraclass Osteodonta

- Superorder Ctenacanthi

- Order Ctenacanthida

- Order Tristychiida

- Superorder Hybodonti

- Order Hybodontida

- Fam. Hybodontidae

- Fam. Ptychodontidae

- Superorder Lamnae

- Order Orthacodontida

- Order Odontaspidida (=Lamniformes Berg excl. Orectolobidae)

- Superfam. Odontaspidoidea

- Fam. Odontaspididae

- Fam. Jaekelotodontidae

- Fam. Otodontidae

- Fam. Carcharodontidae

- Fam. Cretoxyrhinidae

- Fam. Alopiidae

- Superfam. Isuroidea

- Fam. Isuridae

- Fam. Lamiostomatidae

- Superfam. Scapanorhynchidea

- Fam. Scapanorhynchidae

- Fam. Mitsukurinidae

- Superfam. Anacoracoidea

Fig. 1 : Elasmobranch teeth histology. A – Osteodont tooth. B – Ortodont tooth. En – enameloid, ost – osteodentin, ort – ortodentin, p – pulp. After Glickman, 1964a.

L. S. Glickman developed a scientific method for the study of shark evolution based on teeth. Shark teeth are abundant in Phanerozoic rocks starting from the Devonian. Descriptions of genera and species made on the basis of arbitrary sets of characters, which are widespread in paleontology and were so until recently in biology, turned out to be artificial for sharks, which closely resemble to each other. Many sharks that share a large number of characters are not united by phylogenetic links, but have a similar ecological niche instead. The study of extinct sharks turned out to be even more difficult. Attempts to describe generic and specific characters of ancient sharks are made since a long time, but the overwhelming quantity of characters present on shark teeth, and the difficulty to determine the phylogenetic relationships between extinct and extant sharks were the biggest problems of paleontologists. As demonstrated by Glickman, the proportions of the shark’s tooth crown is linked with its feeding behavior, and consequently with its lifestyle. Shark teeth can be subdivided into four groups: clutching (ударно-хватательные in Glickman, 1964a), grasping (колющие), cutting or tearing (режущие, рвущие), and crushing (дробящие). Clutching teeth are conical, elongated relatively to their width, and thick. They characterize sharks adapted to various preys and different habitats (for example Lamna). Grasping teeth are elongated and thin. They are attributed to coastal sharks that feed on small fish and cephalopods (example - Odontaspis). Cutting teeth are wide and thin, while tearing teeth have thick crowns. Such teeth allow to cut or tear flesh, and belong to superpredators (examples are Isurus, Carcharodon, Squalicorax). Crushing teeth are flat or conical but shorter than clutching teeth. They characterize sharks living close to the seafloor and eating molluscs (bivalves as well as cephalopods), small fish, crustaceans(examples are Squatina and Heterodontus). The tooth shape is connected with many other features (such as the shape and disposition of fins), as it has a strong influence on the shark’s lifestyle. In the course of evolution, sharks tend to adapt to new ecological niches, which leads to changes in feeding behavior, so the crown geometry changes to adapt to new functions. Later sharks specialize and ameliorate their tooth functionality (the crown elongates or widens more and more), in the same time secondary adaptation occur, which are linked to tooth overload, lack of space in the jaw and so on (widespread phenomenons : appearance of a lobe on the labial side at the crown-root junction to prevent crown break, atrophy of posterior teeth due to the enlargement of anteriors and laterals). The study of shark teeth is made more difficult by heterodonty – the function of upper and lower, anterior and lateral teeth can be different, and in some cases teeth of different jaw position change at different rates during evolution. The method proposed by L. S. Glickman consists in determining the feeding behavior of extinct sharks based on functional types of teeth, and studying secondary adaptation to these tooth functions. It is possible to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships between extinct shark species, genera and families by studying shark teeth of different age, on the basis of regularities in crown geometry changes during evolution, and secondary adaptation [see 3, 5, 7].

The study of sharks with the method proposed by Glickman demonstrated their high evolution rates. L. S. Glickman started to develop the use of shark teeth in biostratigraphy, which was continued by R. A. Schwajeaite, V. I. Zhelezko and other paleontologists.

- Glickman L. S., 1953: Верхнемеловые позвоночные окрестностей Саратова. Предварительные данные. [Upper cretaceous vertebrates from the Saratov region. Preliminary data, in Russian] // Учёные записки СГУ, 38:51-54.

- Glickman L. S., 1957b: О генетической связи семейств Lamnidae и Odontaspidae и новых родах верхнемеловых ламнид [On the genetic link of the families Lamnidae and Odontaspidae and new genera of upper cretaceous lamnids, in Russian] // Труды геол. музея им. А. П. Карпинского, 1:110-117.

- Glickman L. S., 1958b: О тэмпах эволюции ламноидных акул. [On the rate of evolution of lamnoid sharks, in Russian] // Доклады АН СССР, 123(3):568-571.

- Glickman L. S., 1959: Направление эволюционного развития и экология некоторых групп меловых эласмобранхий. [The direction of evolutionary development and the ecology of some groups of cretaceous elasmobranchs, in Russian] // Труды 2й сессии Всесоюзного палеонтологического общества 226-234.

- Glickman L. S., 1964a: Акулы палеогена и их стратиграфическое значение. [Paleogene sharks and their stratigraphic value, in Russian]. Наука.

- Glickman L. S., 1964b: Подкласс Elasmobranchii. Акуловые. [subclass Elasmobranchii. Sharks, in Russian]. Основы палеонтологии том 11: Бесчелюстные и рыбы 196-237, Наука.

- Glickman L. S., 1980: Эволюция меловых и кайнозойских ламноидных акул. [The evolution of cretaceous and cenozoic lamnoid sharks, in Russian]. Наука.

- Popov, E. V., 2016: An annotated bibliography of the soviet palaeoichtyologist Leonid Glickman (1929–2000) // Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS, 320(1):25–49.

- Popov E. V. and Glickman E. L., 2016: The life and scientific heritage of Leonid Sergeyevich Glickman (1929-2000) [in Russian]. Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS, 320(1):4-24.

Ammonite Cantabrigites aff. cantabrigense. Albien (Crétacé inférieur), Jura. Image from the gallery

Ammonite Cantabrigites aff. cantabrigense. Albien (Crétacé inférieur), Jura. Image from the gallery